"The removal of ice from a De-Icer surface depends on the true adhesion of ice to rubber..." 4

Image from “Engineering Summary of Airframe Icing Technical Data” ADS-4, 1963.

Summary

Pneumatic boot deicers were the first widely used form of aircraft ice protection, and are still used today.

Key Points

- Deicing boots were developed independent of NACA.

- Oil coatings aid the shedding of ice.

- NACA development efforts largely shifted to thermal deicing in the 1940s.

Introduction

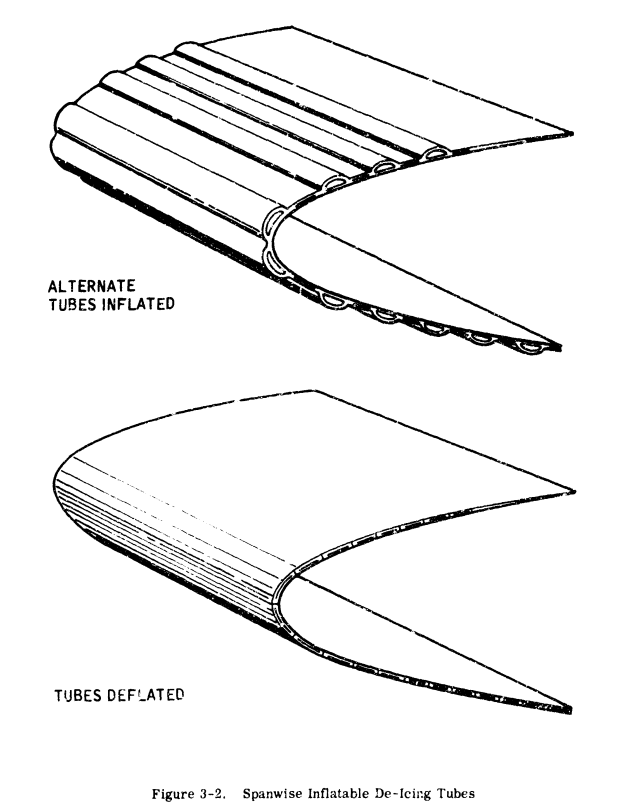

As detailed in "We Freeze to Please": A History of NASA's Icing Research Tunnel and the Quest for Flight Safety, the “expanding rubber sheet” or “ice-removing overshoe” for ice protection was developed independently of NACA in the 1930s, and was the first widely used method of aircraft ice protection. Small passages within the rubber could be periodically inflated to shed ice (typically once every two minutes). While some "inter-cycle" ice forms, the maximum amount of ice is limited, if all is working properly. The original version used rubber "Coated with a mixture of 4 parts pine, 4 parts diethylthalate, and 1 part castor oil". An oil coating improves the effective shedding of ice from the rubber surface, as on a bare rubber surface residual ice can persist and grow between deicing cycles.

While the initial implementation of this method of ice protection showed promise, an accident in 1937 attributed to icing in flight prompted a call for improvements.

Notes on spelling

NACA-era sources tend to use the spelling "de-ice" or "de-icer",

while more recently "deice" or "deicer" tends to be used.

When quoting text from the NACA-era, I leave it as is.

When discussing text of the NACA-era, I tend to use their spelling,

but I may not be consistent.

However, "anti-ice" should consistently include the hyphen.

I am not going to mark every historic spelling variation with "sic".

I read somewhere that NACA was usually pronounced as the separate letters, "N A C A", rather than as a word, as NASA usually is. This explains why the article "an" is used, as in "an NACA 0011 airfoil". However, my aerospace colleagues in the late 1980s, including the senior ones, pronounced NACA as a word.

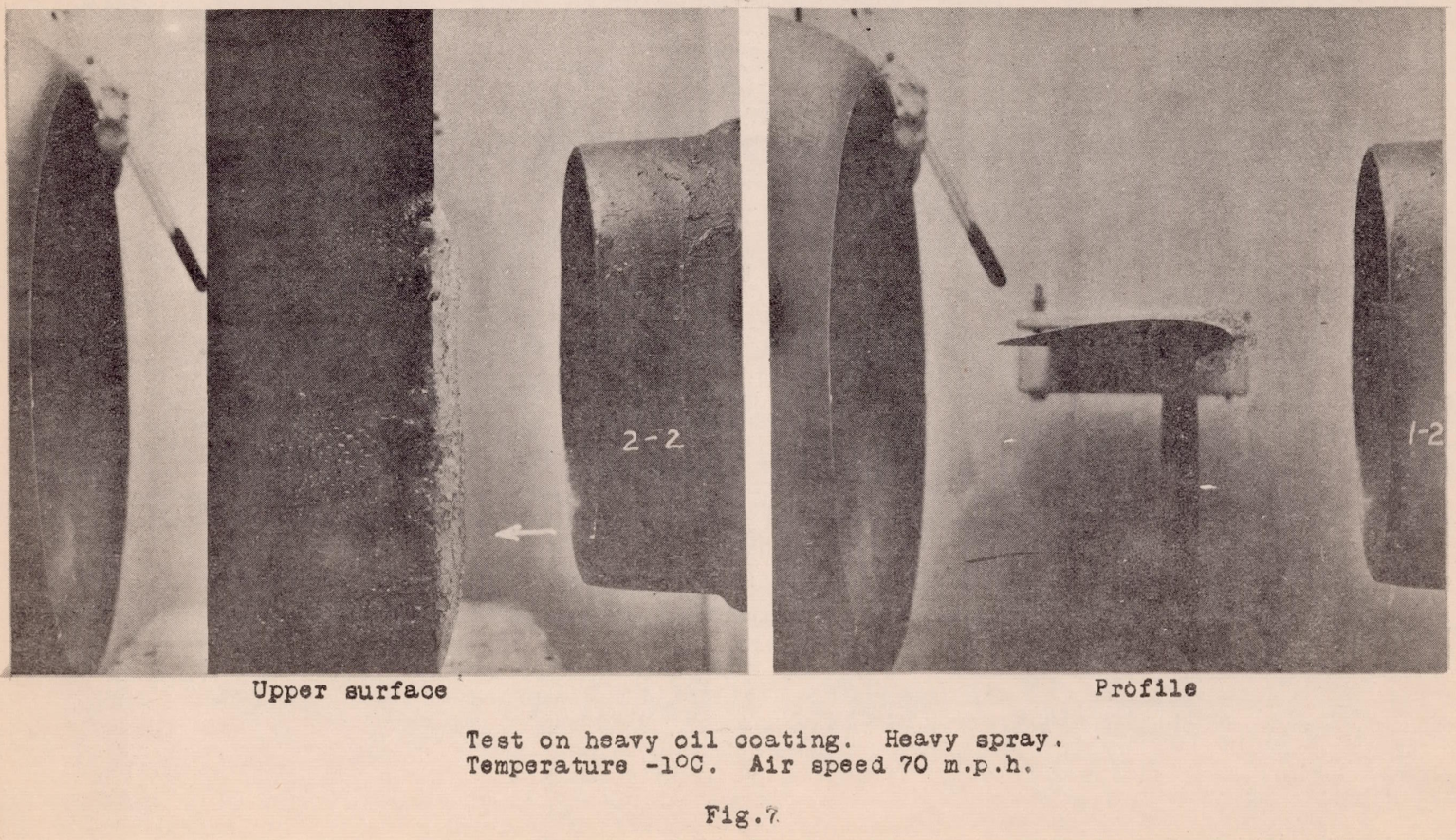

NACA-TN-339 "Refrigerated Wind Tunnel Tests on Surface Coatings for Preventing Ice Formation" 1

NACA had researched several coatings that can reduce ice adhesion, compared to bare rubber or metal (See NACA-TN-339, "Refrigerated Wind Tunnel Tests on Surface Coatings for Preventing Ice Formation").

Insoluble compounds:

- Light lubricating mineral oil.

- Heavy lubricating mineral oil.

- Cup grease.

- Vaseline.

- Paraffin.

- Simonize wax.Soluble compounds:

- Glycerine.

- Glycerine and calcium chloride.

- Molasses and calcium chloride.

- Hardened sugar solution.

- Hardened glucose solution.

However, none of the materials tested lowered ice adhesion enough to shed by aerodynamic forces alone.

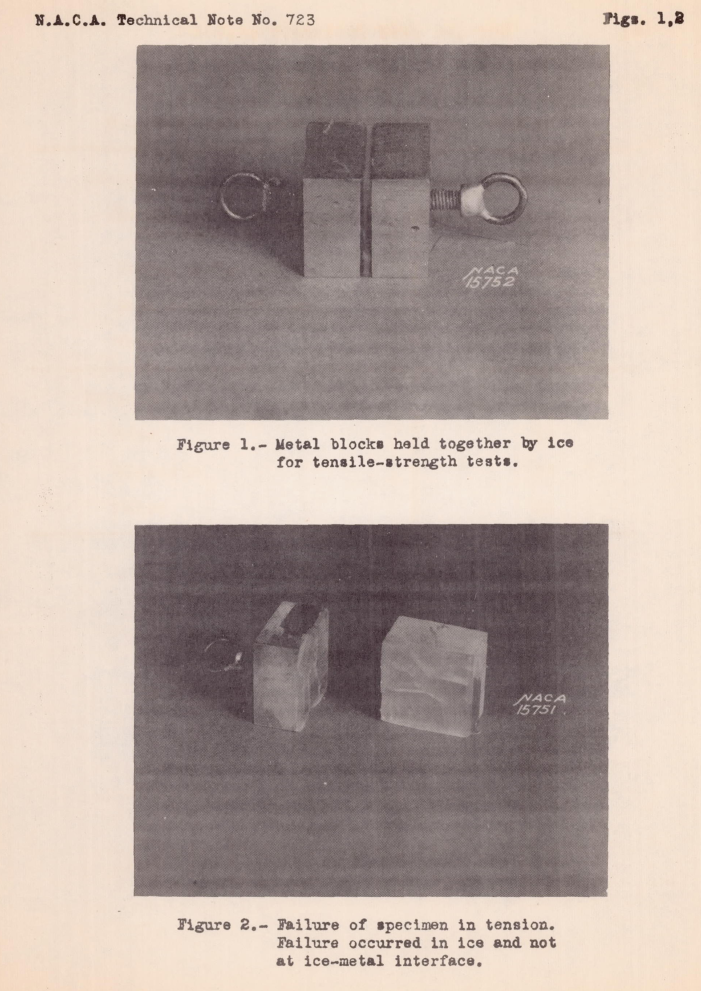

NACA-TN-723 "Adhesion of Ice in Its Relation to the De-icing of Airplanes" 2

The various possible means of preventing ice adhesion on airplane surfaces are critically reviewed. Results are presented of tests of the adhesive forces between ice and various solid and liquid surfaces.

It is concluded that the de-icing of airplane wings by heat from the engine exhaust shows sufficient promise to warrant full-scale tests. For propellers, at least, and possibly for certain small areas such as windshields, radio masts, etc., the use of de-icing or adhesion-preventing liquids will provide the best means of protection.

CONCLUSIONS

The most important conclusions drawn from the present tests are possibly not new, but they seem to be quite definite.

1. Ice will adhere to any solid surface tried thus far with a force greater than the cohesive forces within the ice.

2.Ice will not adhere to a surface provided that there is a liquid interface between the ice and the surface. If such a liquid interface is formed, the force required to remove the ice will be little more than the aerodynamic or aerostatic forces tending to hold the ice to the surface.

3. The outlook for preventing ice formation on the surfaces of an airplane wing by means of some liquid surface is not encouraging. The amount of liquid required will probably be large and some mechanical force is necessary to overcome the air forces in order to remove the ice. The use of such liquids for windshield de-icing or for small surfaces may be successful.

4. For propellers, where a centrifugal force is always available, the use of liquids for de-icing will probably continue to be the most efficient method.

5. Although wind tunnel tests have indicated that heating the wings of an airplane as a means of preventing ice formation is feasible, no full-scale tests have been made to determine the practicability of the method. It is believed that such tests should be conducted as soon as possible.

This reflects a major NACA effort for the next several years, to develop thermal ice protection systems and conduct full scale flight tests.

NACA-ACR-A-53 3

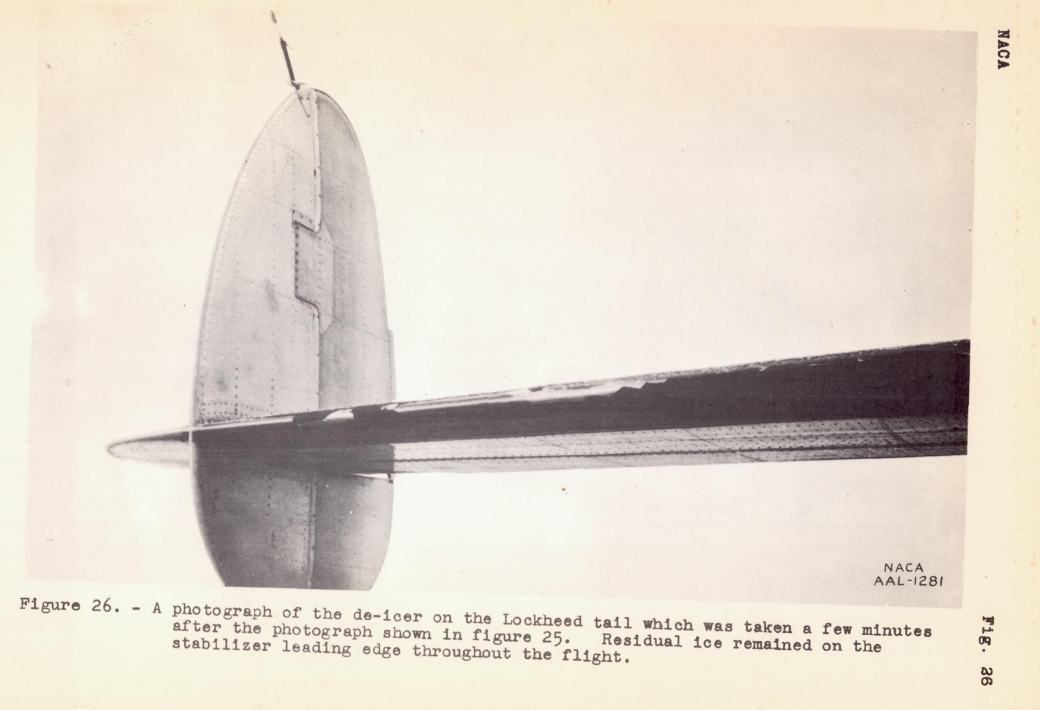

A Lockheed 12A was modified by NACA for flight in icing. This included a pneumatic boot on the horizontal stabilizer.

Ice removal was only partially successful on the horizontal stabilizer on which the inflatable de-icer had been installed. It was observed that if the ice formation was hard and confined to the leading-edge region, upon inflation of the lobes of the de-icer the ice would break into many pieces and blow away. However, if the ice extended rearward over the surface or was inclined to have a soft consistency, the inflation of the lobes would break the ice only slightly and much of the ice would remain on the wing leading edge. Figures 25 and 26 show the ice accretion remaining on the leading edge of the stabilizer after the inflatable de-icer had been operated during one flight.

We will see more of NACA-ACR-A-53 in a future post on engine-exhaust heating.

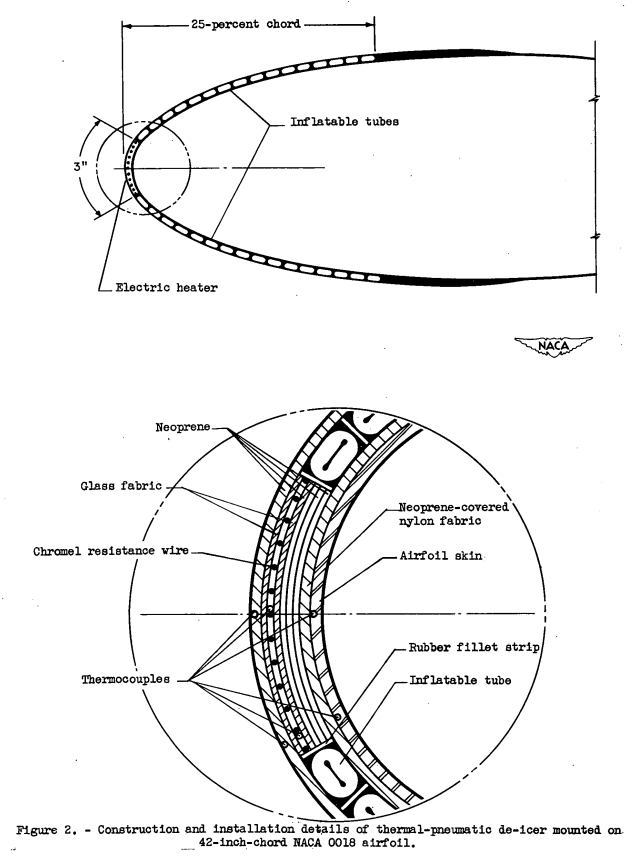

NACA-RM-E50K10a "Effectiveness of Thermal-Pneumatic Airfoil-Ice-Protection System" 4

Icing and drag investigations were conducted in the NACA Lewis icing research tunnel employing a combination thermal-pneumatic de-icer mounted on a 42-inch-chord NACA 0018 airfoil. The de-icer consisted of a 3-inch-wide electrically heated strip symmetrically located about the leading edge with inflatable tubes on the upper and lower airfoil surfaces aft of the heated area. The entire de-icer extended to approximately 25 percent of chord. ...

SUMMARY OF RESULTS

The following results were obtained from an icing investigation conducted in the NACA Lewis icing research tunnel using a thermal-pneumatic de-icer mounted on a 42-inch-chord NACA 0018 airfoil.

1. Excessive ice formation was prevented on the inflatable areas when the pneumatic tubes were operated on a 2-minute inflation cycle with continuous electric heating at the leading edge. 2. During nonicing conditions the installation of the de-icer with no tubes inflated resulted in a drag increase approximately 140 percent greater than that of the bare airfoil. This value increased to a maximum of approximately 620 percent with tube inflation. 3. With complete icing protection on the leading-edge thermal section of the de-icer and with the tubes operating on a-2-minute Inflation cycle, drag measurements indicated that scattered residual ice formations on the pneumatic section after an Inflation cycle produced drag losses approximately equal to the drag incurred by Ice that formed during the remainder of the cycle.

...

I am not aware of this combined system being widely used.

[We may look more at the electro-thermal aspects in a future post.]

Loughborough "Physics of mechanical removal of ice from aircraft"

Loughborough 5 6 detailed some mathematics of ice adhesion and ice shedding from a boot.

Ice shedding was found to be aided by applying silicone oil to the surface. However, effectiveness dropped off quickly after about 20 deicing cycles.

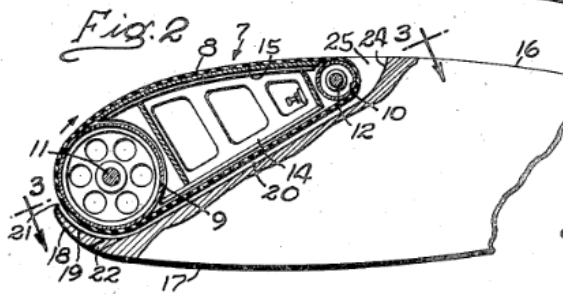

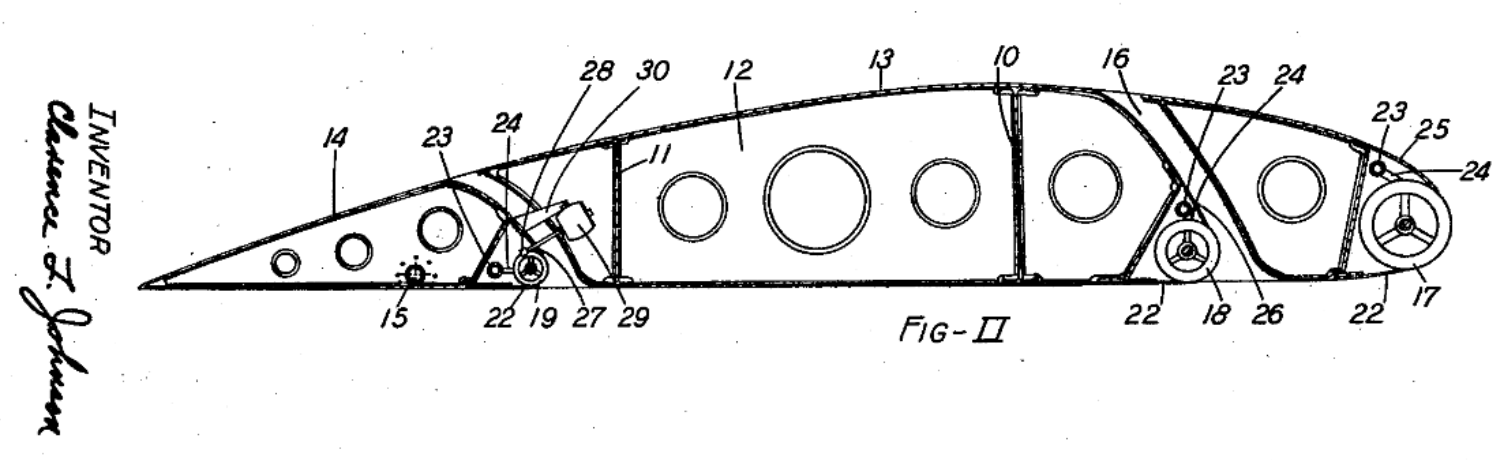

Loughborough 6 also surveys several other mechanisms that might shed ice, (I do not know that any of these were actually built) two of which are included below.

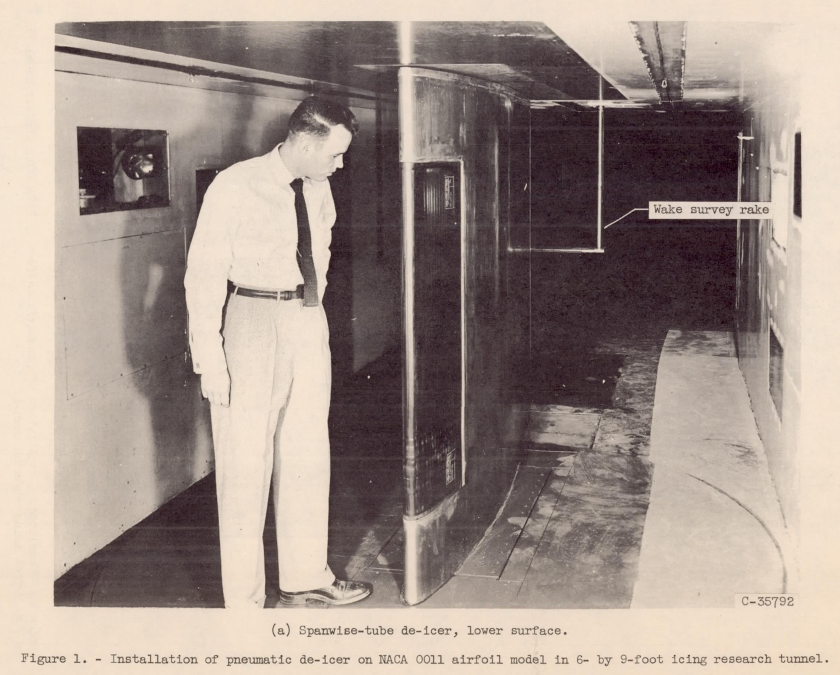

NACA-TN-3564 "Effect of Pneumatic De-Icers and Ice Formations on Aerodynamic Characteristics of an Airfoil" 7

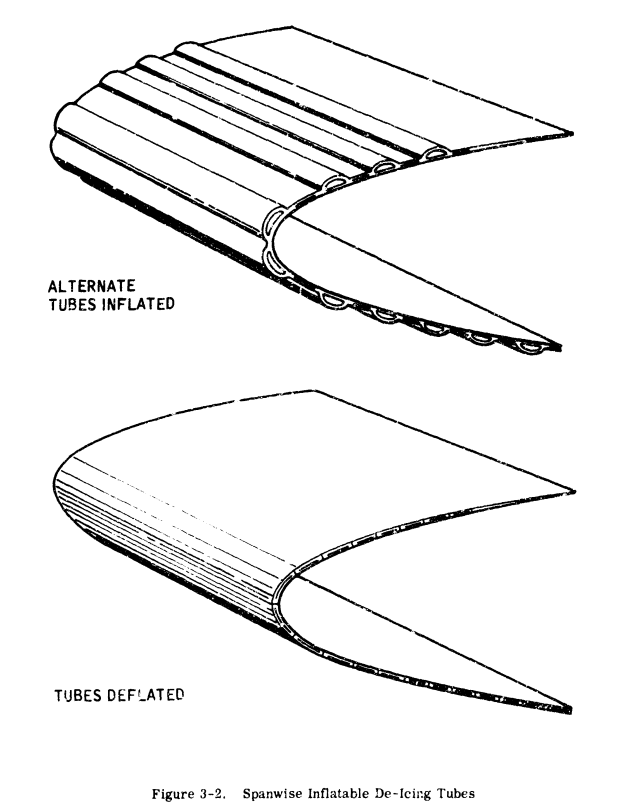

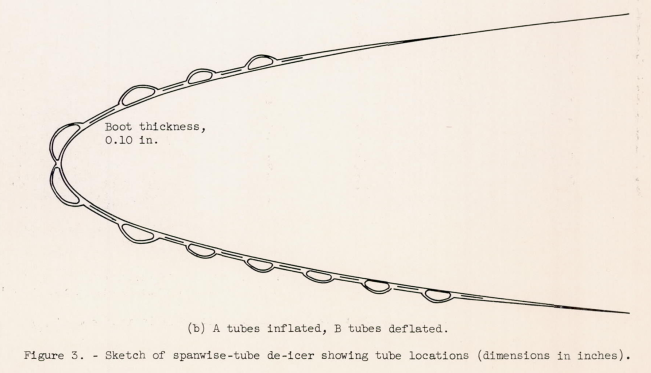

Measurements of lift , drag, and pitching moment of an NACA 0011 airfoil were made in icing using two types of pneumatic de-icers, one having spanwise inflatable tubes and the other having chordwise tubes. ...

NACA-TN-3564 investigated the de-icing performance of a pneumatic de-icer, and the drag caused by the boot in different inflation configurations.

Findings are summarized:

SUMMARY OF RESULTS

The results of a study to determine the effects of pneumatic de-icers and ice formations on aerodynamic characteristics of an NACA 0011 airfoil may be summarized as follows:

1. Boot inflation removes the main part of an ice formation. Ice remaining after inflation of a spanwise-tube de-icer increased airfoil section drag 7 to 37 percent for the following conditions: angles of attack from 0° to 4.6°; airspeeds of 175 and 275 mph; glaze- and rime-icing conditions; air total temperatures from 0 F to 30 F; liquid-water contents from 0.3 to 1.0 gram per cubic meter; and cycle times from 1 to 4 minutes. For these conditions the drag increase depended primarily on chordwise extent of residual ice. In heavy glaze-icing conditions (1.0 g/cu m liquid-water content and 25 F air total temperature) at high angles of attack (4.6° to 9.3°) ice remaining after inflation increased airfoil drag 15 to 100 percent. For a given operating condi tion) the drag increase due to residual ice usually was constant regardless of the number of de-icing cycles. Minimum airfoil drag in icing (averaged over a de-icing cycle) was usually obtained with a short (about 1 min) de-icing cycle. Alternate tube inflation of the spanwise de-icer in dry air increased airfoil section drag 100 to 165 percent and decreased lift 6 to 10 percent . Averaged over a 1-minute cycle) the drag increase with alternate inflation in dry air varied from 10 to 16 percent. Simultaneous tube inflation reduced the 10-percent increase to 3.2 percent.

2. Ice-removal characteristics of a chordwise-tube de-icer were the same as for the spanwise-tube de-icer. Minimum airfoil drag in icing using the chordwise de-icer was always obtained with a short (1 min) de-icing cycle. Inflation of the chordwise de-icer in dry air increased section drag only 5 percent) had no effect on lift) and had negligible effect on airfoil drag averaged over a cycle.

3. With the de-icer inoperative, rime-ice formations of 0.5 pound per foot span increased section drag 38 to 67 percent and decreased lift up to 4 percent for angles of attack from 0° to 4.6°. The same amount of ridge-type glaze ice increased drag 124 to 230 percent and decreased lift up to 20 percent for angles of attack from 0° to 9.3°. Increasing the airfoil angle of attack with even a small ice formation on the airfoil can cause large increases in drag and losses in lift. Spanwise spoilers mounted at various chordwise positions were used to help determine the effect of size and location of ridge-type ice on airfoil drag. Such drag was found to vary almost directly with spoiler height and the local air velocity over the bare airfoil.

Also note that the author Bowden is also an author of the later ADS-4 8.

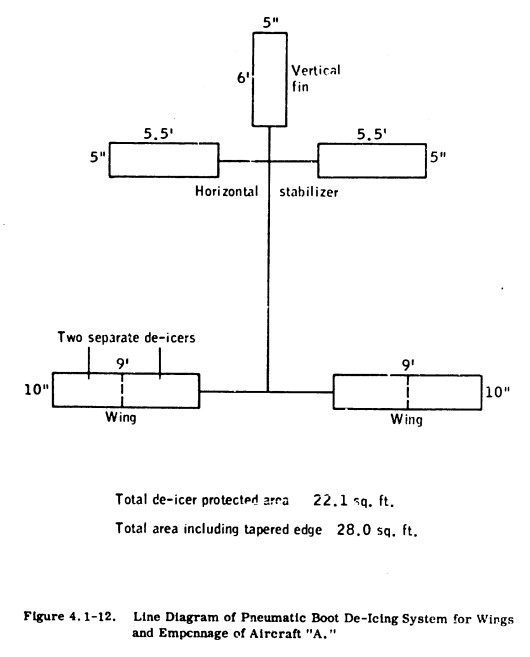

ADS-4, “Engineering Summary of Airframe Icing Technical Data” 8

ADS-4 was review previously in the Thermodynamics Thread.

ADS-4 has a section discussion mechanical deicing systems, and examples of the application to aircraft.

ADS-4 trained at least one generation (if not several) of engineers on aircraft icing (myself included).

Conclusions

Pneumatic deicing boots are still used today on many aircraft. More recent implementations use synthetic elastomers rather than natural rubber, and a variety of coatings to limit ice adhesion. However, for higher airspeed aircraft such as jets, rain and dust erosion are challenges to the durability of the elastomer surface, and other forms of ice protection are more common.

Citations

An online search (scholar.google.com) found

9 citations of NACA-TN-339,

3 for NACA-TN-723,

0 for NACA-ACR-A-53,

18 for "Physics of mechanical removal of ice from aircraft",

0 for "Mechanical De-Icing Systems",

3 for NACA-RM-E50K10a,

40 for NACA-TN-3564,

and 64 for ADS-4.

Notes

-

Knight, Montgomery, and Clay, William C.: Refrigerated Wind Tunnel Tests on Surface Coatings for Preventing Ice Formation. NACA-TN-339, 1930 ntrs.nasa.gov. ↩

-

Rothrick, A. M., Selden, R.: Adhesion of Ice in Its Relation to the De-icing of Airplanes. NACA-TN-723, 1939. ntrs.nasa.gov ↩

-

Rodert, Lewis A., and Jackson, Richard: Preliminary Report on Flight Tests of an Airplane having Exhaust-Heated Wings. NACA-ACR-A-53, April 1941. ntrs.nasa.gov ↩

-

Gowan, W. H., Jr., and Mulholland, D. R.: Effectiveness of Thermal-Pneumatic Airfoil-Ice-Protection System. NACA-RM-E50K10a, 1951. ntrs.nasa.gov ↩↩

-

Loughborough, D. L., Physics of mechanical removal of ice from aircraft, Aeronautical Engineering Review, v11, n2 (Feb 1952) 29-34 [Unfortunately, this does not include the instructive Slide 13 "Most practical de-icers I ever saw" figure in the next Loughborough citation.] us.archive.org ↩

-

Loughborough, D. L.: Mechanical De-Icing Systems, (B. F. Goodrich Company), Lecture No. 10, University of Michigan Airplane Icing Information Course, 1953. (58 pages) ↩↩

-

Bowden, Dean T.: Effect of Pneumatic De-Icers and Ice Formations on Aerodynamic Characteristics of an Airfoil. NACA-TN-3564, 1956. ntrs.nasa.gov ↩

-

Bowden, D.T, et.al., “Engineering Summary of Airframe Icing Technical Data”, FAA Technical Report ADS-4, General Dynamics/Convair, San Diego, California, 1964. apps.dtic.mil ↩↩